Elves, Hobbits and the Image of God

How Tolkien's creatures can help us restore a bit of Eden in our lives.

This is part 2 in a series looking at the Inklings and their environmental warnings for the modern world. Before scientists started raising the alarm in 1955 about the effects of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, or the acidification of the oceans, a group of British writers called “The Inklings” saw that there was something wrong with the way in which we were relating to the natural world. In the previous article, we examined lesser-known inkling Dorothy L. Sayers’ thoughts on the distorted view of work that had captured the modern psyche, and how this has led to excess waste that is destroying people’s lives, as well as the planet.

This article will provide a needed background for the warnings J.R.R. Tolkien has for us. Because Tolkien has a significant positive environmental vision, it will be important to examine how things ought to be in Tolkien’s thought before we can unpack how things go wrong. By analyzing this positive vision, we will better understand the corrupted image we find in Tolkien’s visions of Sauron and his orcish societies and his own warning to the world.

Hobbits & Elves: True Stewards of the Land

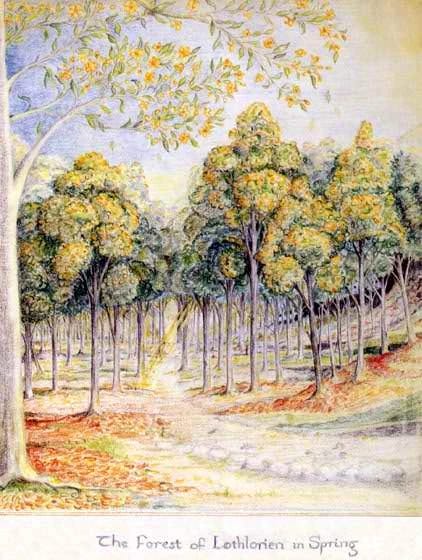

The fact that Tolkien communicates a clear love for nature throughout his mythology is not a secret to those with even a passing familiarity with his work. The images of the rolling grasslands of the Shire, the mysterious, ancient hallowedness of Fangorn Forest, and the Golden forests of Lothlorien drawn from the text and captured beautifully in Peter Jackson’s films have cemented these places in the western cultural imagination. However, Tolkien’s love for nature goes beyond beautiful natural imagery. Rather, it is the thrust behind a robust positive environmental vision.

In Matthew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans’ book Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of J.R.R. Tolkien, the authors discuss Tolkien’s views of stewardship, a theme which extends far beyond environmental considerations, and, above all else, concerns the proper exercise of power and authority. Many elements of Tolkien’s vision of stewardship can be brought out by examining two of his imaginary races, the hobbits and the elves.

Hobbits and Care for the Land

Tolkien’s hobbits occupy the Shire, an idyllic agrarian society, where the residents enjoy the simple comforts of, in the words of Dickerson and Evans, “Food, cheer, song, and well-tilled Earth”1. Part of this simplicity is embodied by their “close friendship with the earth” (Fellowship of the Ring, Prologue), which exemplifies much about Tolkien’s model of environmental stewardship. What can be seen is their rootedness to the Earth, their respect for the natural limits of creation, and a love of their land that leads to a desire to protect it.

Hobbits maintain a rootedness with creation by walking barefoot, since the only craft they are not reported to be skilled at is shoemaking. Rather than tearing up the land to build dwellings, hobbits prefer to live in holes in the ground and view living in constructed buildings to be unnatural.2

While they are tied to an agrarian lifestyle, they are not obsessed with using machinery to make their farming easier, or to exploit as much short-term use out of the land as possible, like modern industrial farming. Tolkien tells us in the prologue that hobbits “do not and did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom” (Fellowship, Pro.). The hobbits’ lack of desire to use machinery to get more out of the land than they need displays a recognition of the land’s natural limits, which the Hobbit farmers of the Shire have come to respect.

This rootedness to the Earth and respect for the land is clearly upheld as an ideal for Tolkien throughout his writings, although he does appear to be critical of their love of comfort which borders on sloth. However, the hobbits are able to be roused out of their sloth by their higher love of their land. This can be seen by recognizing that Frodo’s entire quest is characterized by his desire to save the Shire for others, rather than himself. Also, in The Return of the King, it is a farmer (named Farmer Cotton) and his family that rallies whole of the Shire in defense of the land that has been threatened by evil forces. Tolkien eschews the modern tendency to look down upon farmers and instead views them as particularly wise and prime defenders of the land because of their special connection to it. For both Frodo and Farmer Cotton, their natural love for the land leads them to become defenders of it as part of their stewardship.

Elves and the Beauty of Creation

If the hobbits’ stewardship can be characterized primarily through their sustainable use of creation, the Elven stewardship could be said to be characterized as primarily through the cultivation of the beauty of creation. Whereas the hobbits are famous for their well-tended fields and orchards, the Elves are famous for their beautiful artistry, homes and gardens.

Like the hobbits, the elves do not strip-clear their surroundings, but build within the world as a way of enriching, preserving and protecting its beauty. The elven kingdom which is described in the most detail is Lothlorien, which is depicted in the Lord of the Rings. Called by Legolas, the main elf in the series, “the fairest of all the dwellings of my people”, Lothlorien is a forest of trees where:

“in the autumn their leaves fall not, but turn to gold. Not till the Spring comes and the new green opens do they fall, and then the floor of the wood is golden, and golden is the roof, and its pillars are of silver, for the bark of the trees is smooth and grey.”

In appreciation of this beauty, the elves of Lothlorien build their homes within the trees, rather than cutting them down. They then expertly enhance the area with the careful planting of flowers throughout the elvish kingdom.

While Tolkien seems to criticize the elves for their near total disengagement from the world, the elves of Lothlorien are roused out of their Kingdom in order to defend the beauty that they guard and preserve in their home. During the war in Lord of the Rings, the elves of Lothlorien are described as not only repelling three waves of attacks from Sauron’s armies in the north of Middle-Earth, but the elves lead their army to Sauron’s northern fortress and destroy it, to secure not only the security of their home, but to cleanse the surrounding area of Sauron’s evil influence. For those who are unfamiliar with this part of the story, you can find these events described in Appendix B of Return of the King.3

The Restoration of the World and the Purpose of Elves and Men

While the Hobbits and the Elves have different modes of stewardship, they have a clear unity of purpose. They both have a love of nature, and an appreciation for beauty and gardens. They both have a sense of duty for their land and prefer simple enjoyments like songs and feasts over maximizing wealth and efficiency. They exemplify what Pope Francis’ Laudato Si characterizes as the classical relationship with nature, as he says in Paragraph 106 of Laudato Si:

“Men and women have constantly intervened in nature, but for a long time this meant being in tune with and respecting the possibilities offered by the things themselves. It was a matter of receiving what nature itself allowed, as if from its own hand.” (Laudato Si, Para. 106)

Within these simple, sustainable lifestyles we see that Hobbits and Elves are actually living out the cosmic purpose given to them within Tolkien’s world.

Central to Tolkien’s mythology is the idea that an ancient, primordial beauty existed in the world that was contained within two beautiful trees. It is said in the Silmarillion that “about their fate all the tales of the elder days are woven” (Silmarillion, 38). These trees and their beauty have been lost due to the rebellion of Sauron’s master, Morgoth, who destroyed the trees. The Silmarillion describes how elves and men (and, presumably, Hobbits, who are descendants of men) are called to heal the hurts caused by the loss of this original order. Elves are explicitly given this calling when it is revealed that they should be left to quote “walk as they would in Middle-earth, and with their gifts of skill to order all the lands and heal their hurts.” (Silmarillion, 52).

The Elves, who maintain some memory of this lost world, seek to provide echoes of it in Middle-Earth. When Frodo enters Lothlorien, Tolkien says:

“… it seemed to him that he had stepped over a bridge of time into a corner of the Elder Days, and was now walking in a world that was no more. In Rivendell there was memory of ancient things; in Lorien the ancient things still lived on in the waking world.” - Fellowship, Bk. II Ch. 7

For Men and Hobbits, the echoes of this world are kept alive by the presence of the elves and in the myths and songs of lost paradise. They share in the restoring of the land by living out proper stewardship in the here and now.

Tolkien’s Faith and His Warning for Us

In laying out these visions, Tolkien is doing something more than merely creating a fantasy world and communicating his romantic ideal for taking care of nature. It is not as Pope Francis says about certain segments of the environmental movement, “romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb”. 4 Tolkien was a serious scholar who was deeply shaped by the power of mythology. Myth is meant to communicate more than stories about Gods and goddesses and heroes. At its best, myth relates the most basic truths of life through stories rather than scholarly argumentation.

Tolkien’s myth is inspired by his deep Catholic faith, and his vision of stewardship is connected to it as well. Humans in our world are meant to be like the elves and hobbits. Caring for our world, respecting its limits, seeking to be cooperators in God’s healing of the world. Our own desires for paradise are rooted in the echoes of Eden that was lost in The Fall and the scriptural promise given to us of a restored world brought about at Christ’s return (Rev. 21 and 22). Our job as Christians is bringing about (in a limited, incomplete sense) the in-breaking of God’s Kingdom now, which happens as we become restored bearers of God’s image.

Like elves, we can participate in this today by providing echoes of paradise through the creation of beauty and our support of it, especially in our churches, which is where heaven and earth meet in the liturgy. Like hobbits, we can be present in the Earth through gardening, and learning to enjoy the simple things rather than accumulating endless material comforts. We can support the preservation of creation by supporting smart policies like those that would help create urban forests and restore greenspaces in our cities and reduce the carbon in the atmosphere that is acidifying our oceans and warming our planet. All of these things are part of living out our call to be reflections of God in the world and play a role in the restoration of the world.

Tolkien’s Warning

While many people are undoubtedly moved by the beauty shown to us in the communities of the hobbits and elves and hopefully recognize Tolkien’s environmental vision that is communicated there, we should not ignore the vast evil and darkness present in Tolkien’s world. This is also key to Tolkien’s environmental vision.

Tolkien has a warning that the same power that helped corrupt the lost paradise is present today and is trying to spread. This is typified by the orcs, Tolkien’s evil creatures, and the spread of their armies, but this power also threatens to corrupt the men, hobbits and elves in the world. The next article will examine Tolkien’s warning that when we fail to exercise stewardship over nature, our own human nature becomes corrupted, and we become less than humans. In other words, we risk becoming orcs.

Matthew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans, Ents, Elves, and Eriador: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Environmental Vision, 11.

Appendix F of The Return of the King reveals that the word Hobbit comes from a derivative of the combination of the two Old English words hol, meaning hole, and bytla (meaning building or dwelling), so the Hobbits are holbytla, or, hole dwellers. The Prologue reveals that by the time of the Lord of the Rings, most Hobbits did not live in holes anymore.

These events are briefly described in Appendix B of The Return of the King.

This is the critique given by Pope Francis in Laudato Si, paragraph 19 towards people who want to heal our relationship with the environment without healing our relationship with God and others.

Great article loved it !